In Running Your Business

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

British Generics Manufacturers Association (BGMA) commissioned analysis from the Office of Health Economics (OHE) and the London School of Economics (LSE), exploring the potential impact of continuing the current approach to the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS) onwards from 2024 predicts product withdrawals and less competition. Higher prices flow from that. Is this a real issue or an empty threat?

Companies have to pay back a percentage of their branded sales – including branded generics and biosimilars – under the 2019 VPAS to ensure the NHS branded medicines bill grows no more than 2 per cent a year.

The percentage that drives the rebates – effectively a sales tax – has been rising as spending by the NHS has increased. In the first year of the deal, companies paid back 9.6 per cent of branded medicines sales. For 2023, 26.5 per cent has been confirmed. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) says that this is likely to mean a £3.3 billion in payback in 2023, equivalent to what was paid back from 2019 through to Q3 of 2022.

Driving margins too low?

Companies having to pay back over a quarter of their sales to the Government in 2023 are going to face lower margins. The key question is, how low can they go? And what happens if paybacks continue in the successor deal that is due to run from 2024 to 2028?

The BGMA has said that, in essence, the margin will be too low for some medicines, resulting in more withdrawals from the UK market and less competition. Prices, in turn, could rise. The bigger the sales tax, the bigger the impact. While it’s no surprise to see gloomy predictions as that is all part of the positioning before negotiations for a successor to the 2019 VPAS, could the negative prediction be true?

The Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) recognises that commercial withdrawal can cause medicines shortages, but it’s only one of 12 factors it identifies. The PSNC is concerned, however. Suraj Shah, PSNC Drug Tariff and reimbursement manager, told P3pharmacy, “We are deeply concerned about the potential impact of further instability in the medicines market. An increase in product withdrawals and shortages will mean that overstretched pharmacy teams will spend even more time sourcing medicines and may need to refer patients back to GPs for an alternative course of treatment.”

Gauging how much of a concern this will be is inherently hard to answer from the outside, since it will inevitably reflect companies’ decision-making, as well as external factors. The future seems to be ever more difficult to predict in these perma-crisis times.

Scenario analysis

The BGMA commissioned OHE and Professor Ali McGuire at the LSE to run a scenario analysis to explore the impact of the VPAS in the future, assuming no change from the current version of the Scheme. Their headline output is that the NHS could find itself paying more for medicines because of an indirect impact.

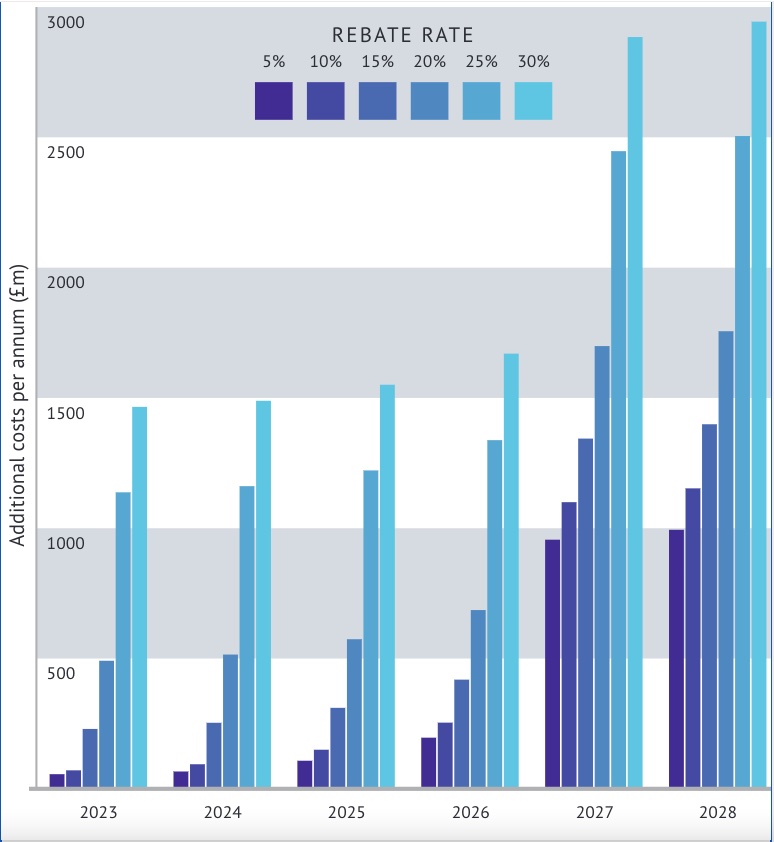

If companies leave the market, that means less competition. Less competition means higher prices when buying from the remaining suppliers. The OHE/LSE predict a higher bill for the NHS, which could more than offset the money VPAS brings in for the Government. Naturally, the higher the sales tax, the worse the predicted result (Figure 1 below).

Scenario analysis is useful because it can provide insights, even if no-one can predict the future precisely. The challenge with the scenario analysis in this review is that the scenarios draw heavily on the results of a BGMA survey, which is a bit like marking your own homework. There’s no surprise that companies who are liable for paying a sales tax say it will hurt them.

To be fair, the OHE/LSE report is clear about its reliance on the BGMA survey, and it’s not the sole driver of their work. They also look to the literature as well. The killer point in the OHE/LSE analysis worth focusing on is that the BGMA asked its members about their expectations for market costs in the future. The analysis suggests companies expect a 17.3 per cent increase in the next five years. This is important because it’s the cumulative impact of inflation, business-as-usual taxes plus the potential for a big VPAS tax on margin that matters. And that makes it look more likely that companies really are questioning whether it’s worth supplying the UK.

Branded generics: in/out?

Unsurprisingly, the BGMA has called for branded generics to be taken out of the scope of the VPAS, which is a simple solution from its perspective. As an alternative, we could review what really needs to be a branded generic, especially given existing concerns about them. They come with the added cost of marketing that unbranded generics don’t. Counterintuitively, however, de-branding can create higher costs too, depending on the market dynamics of the specific molecule.

Another option is making the current mechanisms that deal with uneconomic prices work better. Price rises can be applied for but, to paraphrase the BGMA, seeking a higher price is a burden for companies and comes with no guarantee it will be granted. Price dynamics matter for community pharmacy reimbursement, so a push for efficiency in processes would be a win for them too.

Practicalities matter

For community pharmacies, it matters more that whatever the ripples from VPAS, there is a plan. A ‘hope for the best, plan for the worst’ approach would serve the sector well.

The Department of Health and Social Care says: “There is a team within the department which deals specifically with medicine supply issues, shortages and discontinuations, arising both in the community and hospitals. It works closely with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the pharmaceutical industry, NHS England (NHSE) and others operating in the supply chain, to help prevent shortages and to ensure that the risks to patients are minimised when they do arise.”

The DHSC also told P3pharmacy that it doesn’t report withdrawals internally. It says this happens a lot – for a number of reasons. Manufacturers are obliged to notify the DHSC of product shortages or discontinuations through the discontinuations and shortages (DaSH) portal, so there is a line of sight.

That’s – sort of – reassuring, but for community pharmacy, it matters too that reimbursement, if prices do rise, keeps up. Otherwise, community pharmacy could bear the costs.

As Mr Shah says: “Pharmacy teams are already struggling to obtain stock of several medicines in short supply. Prices of several medicines have also risen over the past few months, and this has added further pressure on contractors because the NHS reimbursement prices of medicines have not kept up with increases in market prices.”